Author:

Green Steps

Short summary:

This article examines a contentious project at the intersection of urban planning, art policy, environmental protection, use of taxpayers' money, and pedagogy. Why does a society make decisions that contradict sustainable development?

Altoona Park and the children's art laboratory, Kikula in short for the German word KinderKunstLabor, have been a bone of contention in St. Pölten for quite some time. A citizens' platform has even demonstrated against it, and the waves rose between the parties in the municipal council. A complex intertwining of problems blocks effective measures against climate change, not only in this city, but worldwide. A few days ago we took a closer look at Altoona Park because on October 24th the municipal council decided to invest more than half a million euros to initiate the preparatory construction measures for building the Kikula.

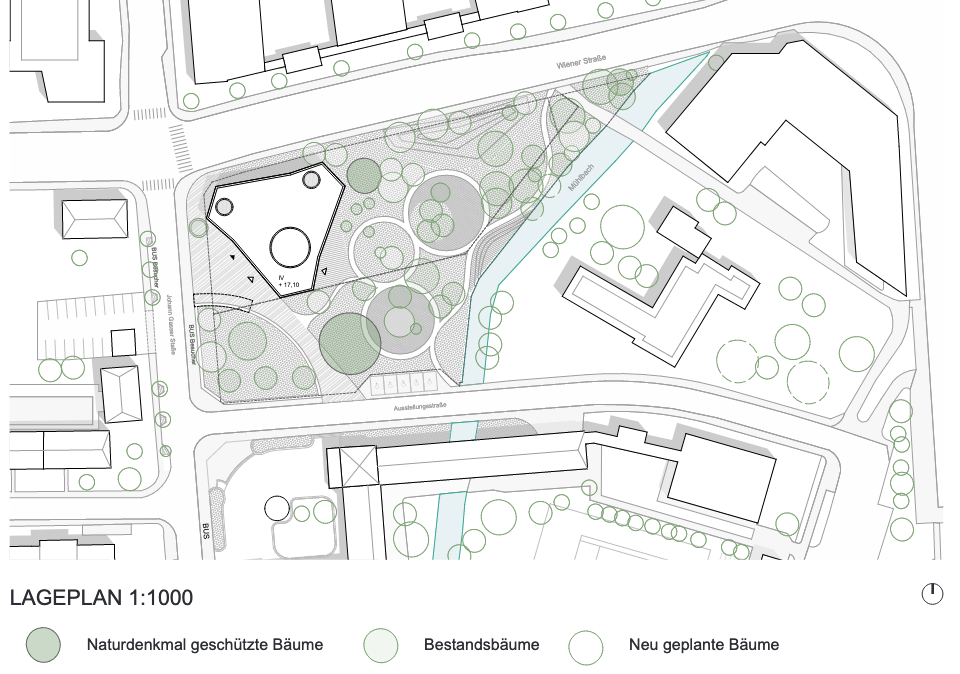

Our ecological report was already published by Gloria Corradini last week, confirming that Altoona Park presents a high tree biodiversity in the city centre, despite being located in an area of only 5500 m2. the Altoona Park in St. Pölten, lacking the existence of a formal botanical garden, comes closest to this definition with the exception of the South Park in the Voith Villa. Indeed, 16 species of trees is an above average number. For comparison, we found only 10 different species in the much larger Hammerpark.

However, this article will focus on the dynamics that led to the decision of building the Kikula in Altoona Park. In order to do that, let's look at why this project has been planned, what's in favor of it, and what's against it. One could say that a beautiful building in the center of the city, where children aged 6-12 dedicate themselves to art, supervised by professional artists, is a great idea and a benefit for the population. The decisions have been made anyway and are unlikely to be changed, so let's take a closer look at this new reality and see what added value and consequential problems it will bring to St. Pölten.

Architecture and children

As a fan of architecture, one must undoubtedly state that St. Pölten lacks modern eye-catchers. Graz has the Kunsthaus, Linz the Lentos, Vienna the Museumsquartier, but the young provincial capital of St. Pölten lacks an innovative building that connects society and needs to fill the existing gap of an architectural "landmark". In this respect, Mayor Stadler is right: "It is not just another cultural institution, but it grounds on a completely new idea, according to which children can come into contact with all forms of art and culture and remain enthusiastic about them throughout their lives. It will be an extremely lively place, a real centre of attraction."

The project of the Swiss architect Michael Salvi's prevailed over more than 40 submissions, likely in part because of its compactness, which fits into the small Altoona park better than some other plans. "Building a house in a park is not commonplace" the architect said. He spoke of a unique task, on the one hand to think radically from a child's perspective, but on the other hand to convey a serious concept of art. "The planners have succeeded in designing an innovative, exciting, ecological architecture that meets the needs of children," said Governor Mikl-Leitner about the design.

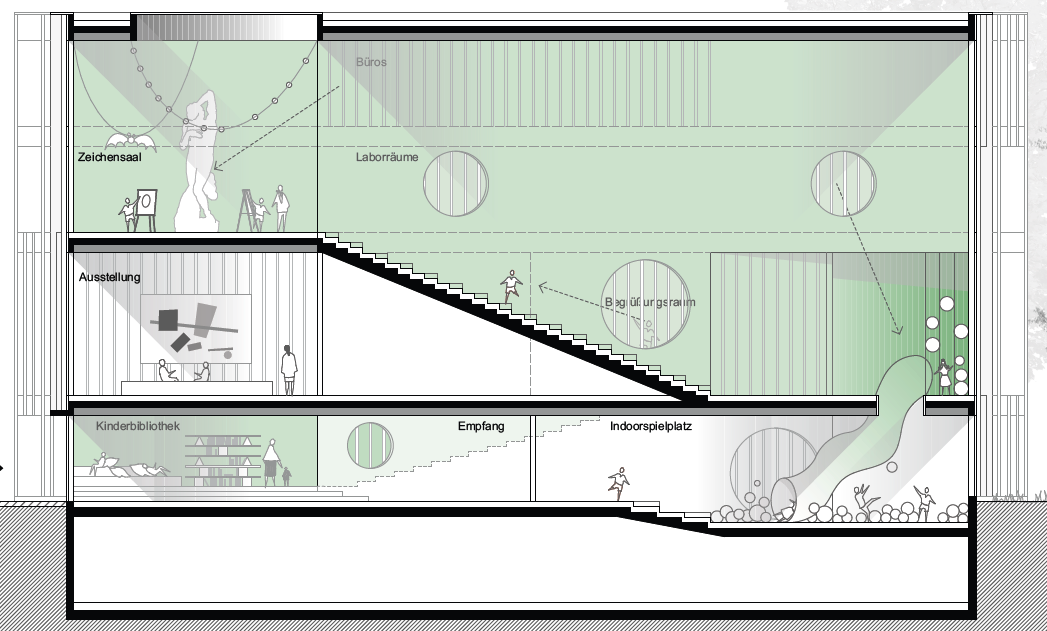

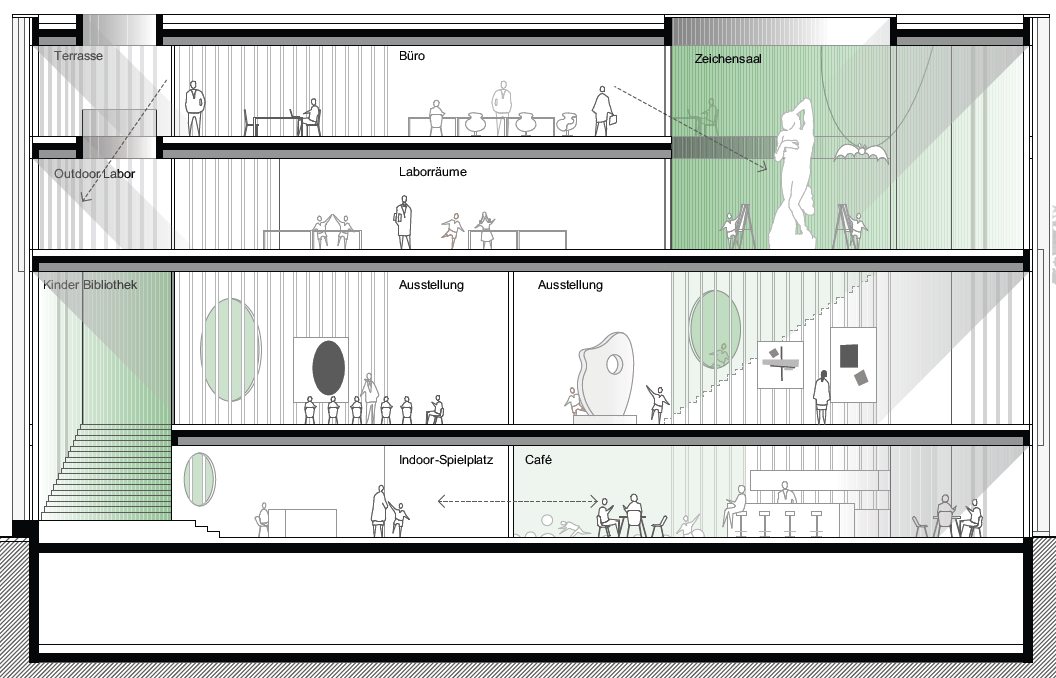

Mikl-Leitner can only be agreed with to a certain extent because whether the building, which will cost 15-17 million euros, really meets the needs of children is questionable. First, actually only the second level and the indoor playground, which takes up one third of the first floor, will be available for children. The third level will be offices, the first level exhibition space and two thirds of the first floor will be dedicated to gastronomy and thus more to adults. Converted to the total area of the building, this is a small proportion. However, if you calculate in volume of space, this proportion is even less because the exhibition areas have higher ceilings than the rest of the premises.

A relatively narrow staircase with more than two full stories of room height is designated as the heart of the building because this area takes the form of an auditorium where events and presentations can be held. While the room height is palatial, the staircase is kept very narrow so that only a few children can sit there, let alone anyone can still pass. It is questionable whether this area will really be used by 6–12-year-olds. Indeed, any educator knows that children of this age would rather be running around or actively working on something, playing with someone, than listening to a lecture in the manner of a student.

The Kikula was conceived as a laboratory, meaning a place where art is actively created. However, the entire level 2 of the building is a museum. People do not work, play or experiment there: they rather exhibit. It would be understandable following the guidelines of the project, but the pedagogue in me asks whether this massive area is useful, because it is difficult to imagine 6-12 year old children looking at the artworks of other children. Hence, level 2 is not for children but for the parents sipping their cappuccino on the ground floor, dropping their kids off at the Ikea-like indoor playground, and letting the children's artwork on display to convince them that it's the right decision to let their offspring work in the lab once a week for a semester or longer.

The drawing room on levels 2 and 3 is inspiring. Flooded with light, it conveys the atmosphere of an artist's studio and can put young minds in a mood as only good architecture can. I can well imagine that one or the other child will turn from commitment to enthusiasm there and, as in Arno Stern's painting place, develop freely. The question remains whether it is right to limit this possibility to the age group of 6-12 years or whether it would make sense to make this new facility available to young people as well.

Site and nature relationship

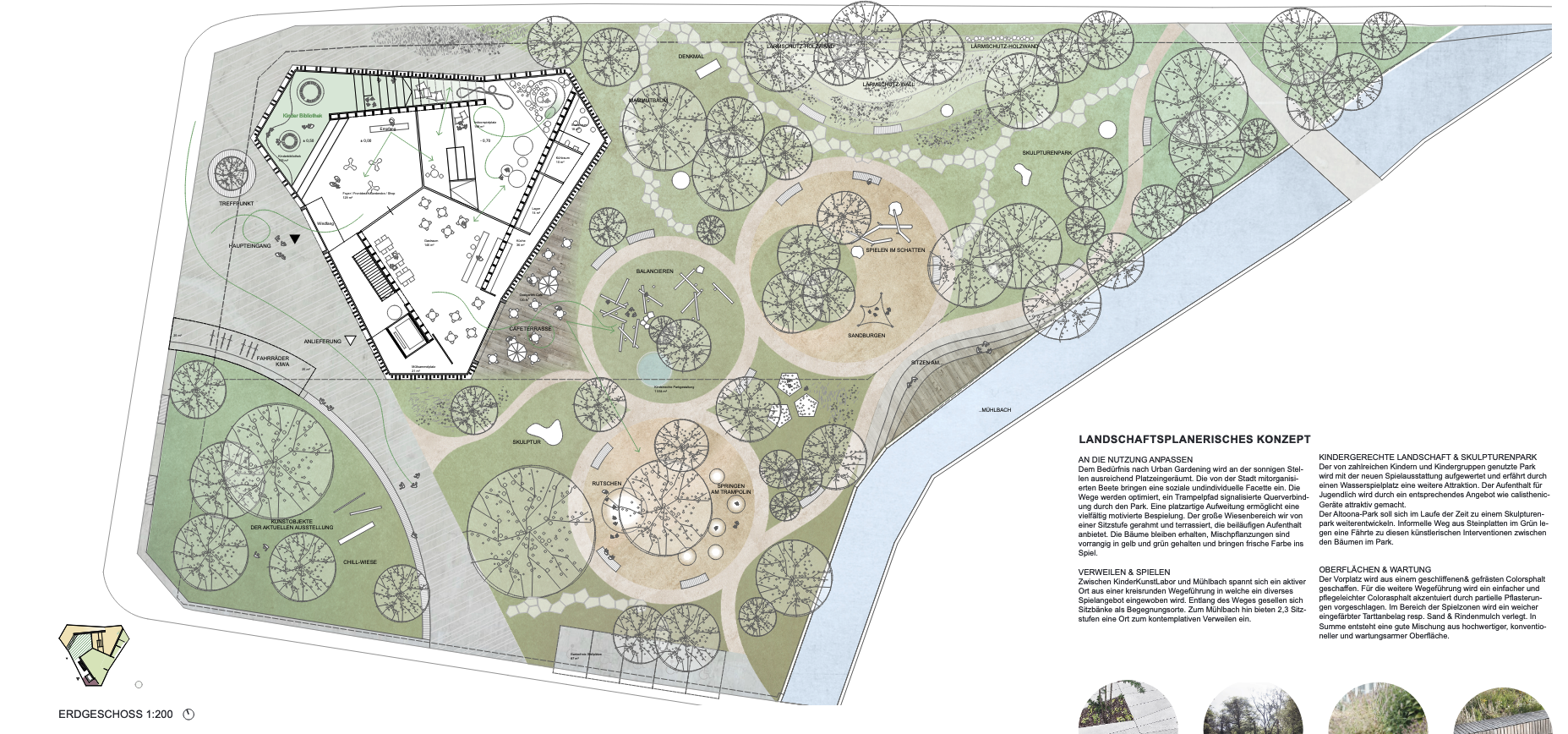

In the choice of Altoona Park as the location for the Kikula - according to media reports - there was a lack of transparency. The proximity to the existing cultural district, i.e. the Museum of Lower Austria and the Festspielhaus, probably tipped the scales - and this is understandable. The busy Schulring makes the park a place where one does not really want to linger. Whether the wooden palisades and the hill will create real noise protection remains to be seen. However, they do not solve one problem: safety. As a father, I wouldn't be able to sit down and relax on the inviting terrace in front of the cafe if the Kikula's outdoor area wasn't fenced off from public roadways.

The adjacent mill stream to the east of the property brings in the element of water, and the planned steps will certainly result in fascinating one child or another, but not because of contemplation as the architect's plan describes. Contemplation is also not a common activity that this age group engages in. Children will make floating objects out of autumn leaves or the many different cones that can be found in Altoona Park, and float them from there toward the Danube. Likewise, on certain days, light boats could be launched. The possibilities are many.

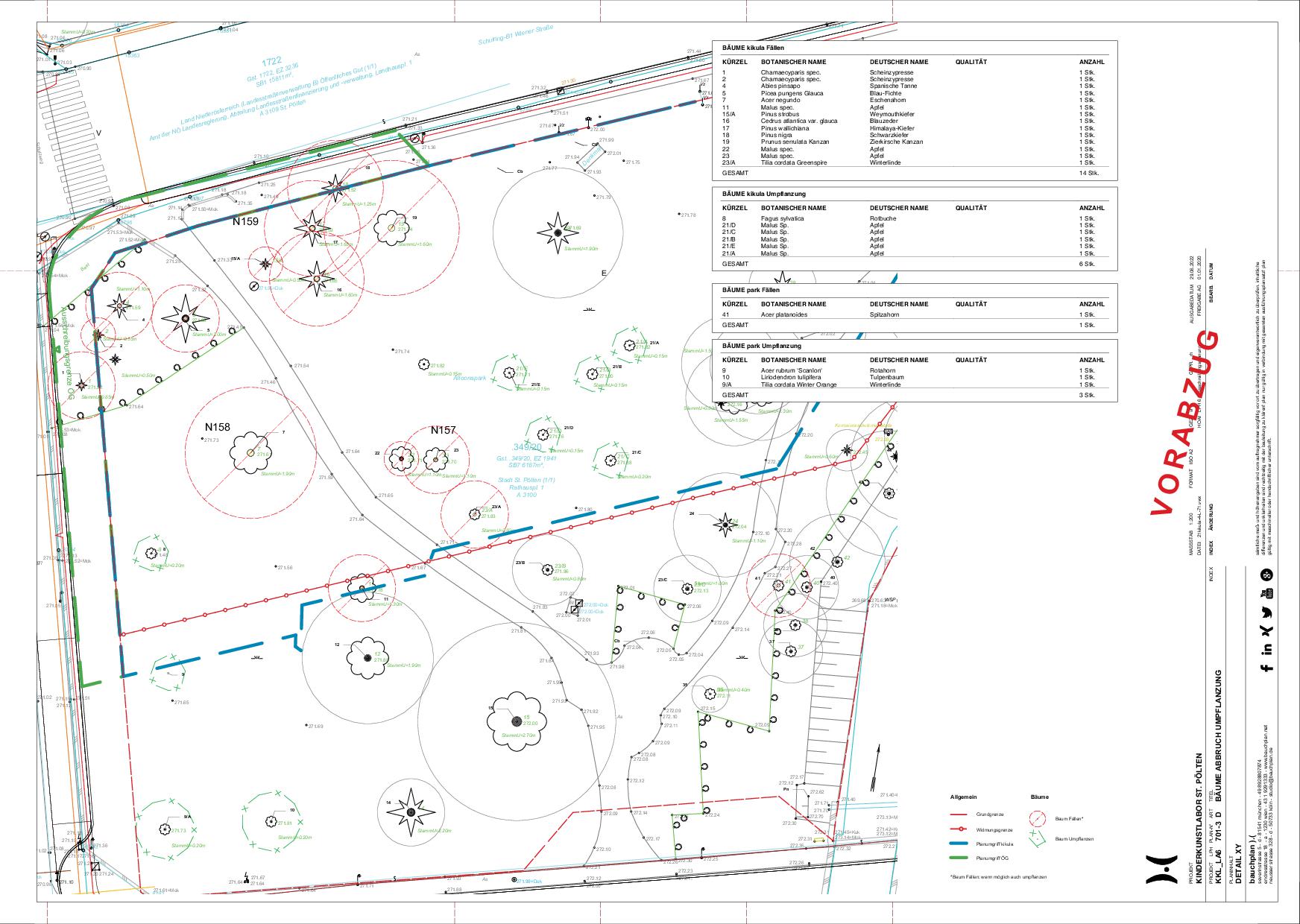

It is interesting to note that the outdoor landscaping plan covers two natural monuments in Altoona Park. The fact is that there is no natural monument in Altoona Park, but a small-leaved lime and a small giant sequoia grow side by side directly across from the Theodor Körner School. In the architects' exterior plan, a redwood tree would be located by the school ring. This error leaves a dubious impression and creates some concern: can the assurances of the developer be trusted that the tree population will not be significantly reduced? How seriously has the outdoor space been considered?

If the plans are to be believed, the Giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) next to the small-leaved lime would not fall victim to the extension of the forecourt in colour asphalt, and the dawn redwood (Metasquoia glyptostroboides) right next to the building near the school ring would remain. The endangered Atlas cedar (Cedrus atlantica) will have to be cut down, as several other medium-sized specimens, and it begs the question of why the building was not placed in the southwest corner of the park. Does noise control justify the removal of some rather substantial trees? If not otherwise possible, it would be very desirable if these trees were not cut down, but moved to the southwestern part of the park as they are here.

What has been given some thought is the design of the forecourt and the pathway, which will be created from ground or milled colour asphalt. According to the plan, it will be a good mix of high-quality, conventional, and low-maintenance surface. We would like to see the southern part of the park not cut by the extended forecourt: the southwestern corner of the park should remain connected to the southeastern part. The small-leaved lime tree will not like the soil compaction that will result from the asphalting.

Despite all the criticism, the park will gain substantially in value as a result of the Kikula. The built-up area will be replaced by a new green space in the immediate vicinity: right next to the Jahn School there used to be tennis courts, which, according to the magistrate, will be converted into a pocket park. A certain noise insulation is possible due to the building and the previously poorly visited park will undoubtedly become much more attractive due to the redesign. It is to be hoped that work will really be done with the tree population and that the relatively wild area next to the mill stream will remain untouched. It is a healthy contrast to the artificial park and gives children the most direct access to nature. The issue of safety and separation from the adjacent streets remains to be answered.

Pedagogy and inclusion

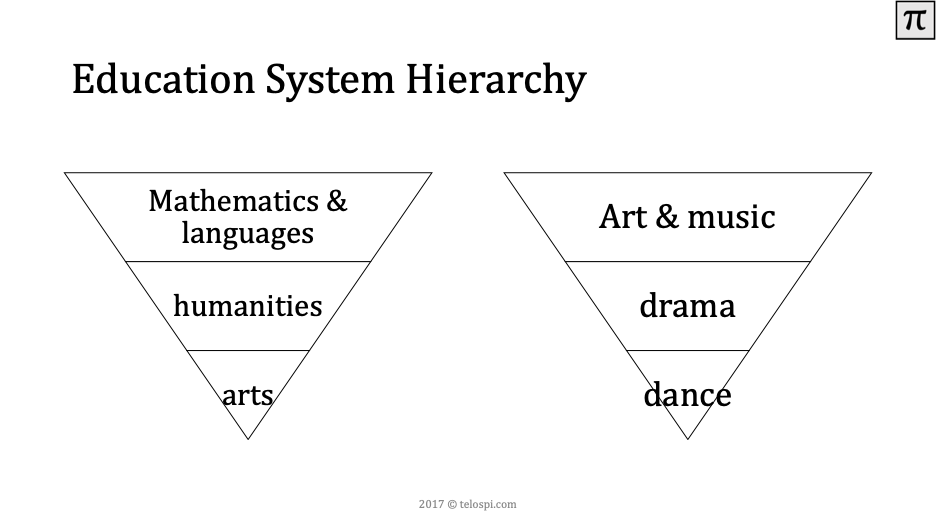

Ken Robinson is known for arguing for equal value in education between STEM and visual and performing arts. He stated that all of the curricula he has studied are subject to a hierarchy that places math and languages above the humanities and ranks the arts as the least desirable skill. Within the arts, again, dance is found at the bottom. But we should abhor the body and revere the spirit. The more intellectual educational content, the better it is commonly seen as suitable for schools.The more physical it is, the less one wants to let children deal with it intensively.

Robinson believes that this one-dimensional approach to education leads to limited creativity and, more importantly, deprives many children early on of the opportunity to find their element. "Education", Robinson says, "in some ways takes many people away from their natural talents. And human resources are like natural resources: they're often buried deep. You must go looking for them; they don't just lie on the surface. You must create the circumstances in which they show themselves.”

The Kikula can create such circumstances, and I am convinced of that, but if we realistically consider for how many children and to what extent in time this will be the case, we must ask ourselves whether this considerable sum of tax money has been used properly and fairly. As an institution, the Kikula is a supplement to the compulsory schools and is not a proper school. It is visited by school classes on a temporary basis, but they have to arrive during school hours, and this makes a repeated art experience at this location somewhat tedious and, loosely based on Robinson, remain a "scratching of the surface" experience. Dedicated parents can send their children to classes in the afternoons, as it is already possible at the city's music school or the state's music and art schools. Thus, Kikula will serve a more elite audience, joining the ranks of institutions dividing rather than uniting societies.

Inclusive education is decentralized. It is planned and emerges where children spend the majority of their time; for the target group of 6-12 year olds, this space is mostly close to home. If money were no object, then the Kikula would have to be preceded by Tinkering School-like equipment in all existing schools or people's homes, where children are introduced to handicraft skills, creative planning, sustainable repair and much more. All those activities that are fun and meaningful, but for which there is no space in schools. The Kikula is the crowning glory of such an infrastructure, but not the foundation.

In the parallel process of the urban climate strategy, the vacancy analysis was noted as an essential measure to slow down climate change locally. Renovating people's homes, e.g. the one in Viehofen, would make neighbourhoods more attractive instead of focusing all energy on the already overloaded city center. Children could experience art directly in their neighbourhood if local resources are activated accordingly. The costs for the renovation and the additional equipment of neglected schools such as the NMS Viehofen are undoubtedly much lower and the example of the Volksheim Viehofen shows that sometimes an absolutely safe garden is also included.

Art is generally perceived as elitist because only the wealthy can afford the time to practice it and the money to acquire it. But like science, art is a phenomenon that needs to thrive across the breadth of society. By choosing a Berlin art professor as the artistic director for Kikula, they are sending an indirect message to the population: art is elitist. Instead of providing local youth and social workers with additional training and appropriate resources, the appointment of an artistic director parallels that of the famous opera houses, where only the name of the artistic director makes the house shimmer.

Pedagogy functions differently - especially in the age group in question. On the one hand, it is the space and the possibilities that are opened to the child on a daily basis. On the other hand, it is the educators who spend time with children on a daily or frequent basis who allow them to grow and shine. They can respond to children holistically because they take the time to understand children holistically, with their problems, limitations, talents and interests. Such things are difficult, if possible at all, in a place you visit fewer times in a year. Even in the regular classroom, it is a challenge as a teacher to address the diverse needs of children and, again following Robinson, to help them access their element.

So, if one really wanted to rethink education in St. Pölten, this enormous sum should have been used differently. More teaching staff in the city schools and smaller classes to achieve better supervision ratios. Three-dimensional learning to help children with a migration background gain a foothold in the German language more quickly. Many educational measures come to mind on an ad hoc basis that we would have addressed as decision-makers before Project Kikula. In this context, it is curious that the city lacks 20 million for cost-of-living adjustment, i.e., funding for basic needs is not secured, and demands it from the federal government, while with impressive determination an equally large sum is freed up for a centrally conceived temple of art. The Kikula thus reflects locally what has been observed globally for several years: we distribute from the bottom up instead of making our societies fairer.

Pedagogy and POWER

This distribution policy contradicts basic socialist values and appears to be a political impossibility in a traditional working-class city - and yet the Kikula is becoming a reality. What is the motivation behind such decisions? Why is the Christian Social regional government allying itself with the Social Democratic city government for this project? The answer is provided by the second Viennese school of psychotherapy, which recognized power as the drive for human action, not in the libido, as Freud did, but according to Alfred Adler.

A look at the structure of the municipal and those enterprises in the country shows that instead of decentralized cultural support, institutions have been built up for years that concentrate power in the field of art and culture. The Plexiglas stands that display the cultural offerings in St. Pölten at a wide variety of locations do not show a diverse cultural landscape supported by taxpayers' money, but rather cultural institutions funded exclusively by taxpayers' money that are owned by the city and the state. In St. Pölten and Lower Austria, there is almost a state monopoly on culture, which does not give truly creative minds any room for creation.

An established St. Pölten resident properly described the situation in the summer: "Besides the experiments in the Seedose and Sonnenpark, there is no free scene in the city. It's all under control." This state of affairs will be further worsened by the Kikula, ME, as it will undermine the financially strapped Sonnenpark and the climate research lab located there. Just like the Kulturheim Viehofen, the buildings of the Sonnenpark are in serious need of renovation. Unlike the Viehofen Cultural Center, however, there is no need to create a local cultural movement at the Sonnenpark: it has already existed there for 20 years. Neither the city nor the state have sufficiently supported this important grassroots initiative. Not even a Nextbike stand has been installed there.

An awake citizen must realize (and many already have) that an absolutely governed country and city are the problem behind the Kikula. We point our fingers at China, where a party leader whose name may no longer be pronounced secured a third term in office. We read in various media how we must support the defense of democracy. In our own backyard, however, we fail to live true participation. A change in the relevant laws, which limit the terms of office of city and state politicians to a maximum of two legislative terms, is overdue.

Read more:

• https://www.meinbezirk.at/st-poelten/c-lokales/kikula-im-altoonapark-protestkundgebung-von-buergern_a3699753

• https://www.meinbezirk.at/st-poelten/c-politik/spoe-braucht-sich-ueber-proteste-nicht-wundern_a4680254

• https://kurier.at/chronik/niederoesterreich/sankt-poelten/polit-eklat-um-12-millionen-euro-teures-projekt-in-st-poelten/401398398

• https://www.st-poelten.at/news/presse/17508-beschluesse-im-stadtsenat-und-gemeinderat-vom-24-oktober

• https://m.noen.at/st-poelten/st-poelten-344-stimmen-fuer-das-kikula-st-poelten-kikula-altoona-park-redaktion-268150446

• https://noe.orf.at/stories/3093136/

• https://www.facebook.com/stpoelten/photos/a.120296326077140/278324856940952/?type=3

• https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hhh-fcZKox4

• https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ken_robinson_do_schools_kill_creativity

• https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/16158494-finding-your-element

• https://www.tinkeringschool.com/